Malachite - A Human History Gem

A vivid to dark green color catches your eye. Beautifully banded in pastel to deeply saturated green to maybe a bit of bluish green. Once you’ve seen it, you never forget it. Just about everyone recognizes this distinctive gemstone – malachite!

WHAT

Malachite is a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral [Cu2(CO3)(OH2)]. Copper gives it the strong green color the gem is prized for and its weightiness. The carbonate hydroxide results in its being on the soft side (3.5 to 4.0 Mohs hardness scale). The variations in color, from light to dark, reflect changes in the relative concentration of copper and carbonate in the water while the mineral was precipitated. It often grows as stalactites in underground cavities - similar to those seen in caves. When these are cut, the pattern of banding and orbs displayed can be mesmerizing.

Malachite slice, Kolwezi Mining District, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Arizona, Donated by Nicolai Medvedev, photo - author's own

As a gemstone, malachite is fairly soft. This means it can scratch during everyday activities, so it’s best use is in earrings or pendants where it’s less likely to be banged against harder objects. Because it’s a type of carbonate, care should also be taken around acidic materials. Do not wear malachite while cleaning with bleach, vinegar, or ammonia or while cooking with acids, especially if wearing it on your hands where the two can come in contact. That said, malachite can, with proper care, be quite durable. Witness the fact that it has been in use as a gemstone for centuries.

Although stunning in its own right, some of the most spectacular examples of malachite include admixtures with other copper minerals formed in the same locality, such as azurite, chrysocolla, and turquoise. The resulting mix of green and blue patterns are sensational!

HISTORY

Malachite has been around as a gemstone for jewelry and or sculptural works for thousands of years. It is thought to be the first ore used to smelt copper metal and the oldest source of green pigment. Today it is still popular, but less valuable than in the past. However, as a modern gemstone with a long, rich history, it stands along with the big 3 precious gems.

Ancient cultures used native copper for centuries. Archeological evidence from around the Great Lakes in North America indicate that ancient Native Americans worked native copper ore at least 9500 yrs ago. This type of copper however is not globally abundant.

Eventually, cultures discovered how to extract copper from copper minerals through smelting. The first of these minerals was malachite, which, in its purest form, contains up to 57% copper. Smelting is a high temperature process in which the metal & nonmetal molecules are disassociated, decomposing the carbonate and converting copper oxide into metal. There is much debate in archeological circles as to when, where, and who first smelted malachite to produce copper. Copper smelting in the Middle East is dated to about 6,500 years ago. Recent finds in Serbia indicate smelting emerged there 7000 yrs ago. In Wales, 3,800 years ago, 1,760 tons of copper were produced from malachite mined at the Great Orme Mines. Evidence also exists that ancient MesoAmericans developed copper smelting independently around 700 AD. In any case, the development of this process was incredibly important. Malachite proved an essential element in ending the Stone Age and eventually, the start of the Bronze Age.

Malachite and azurite mined in the Sinai and ancient Egypt from about 3000-4000 yrs ago were ground into powder to produce green and blue makeup and pigments for painting on tombs. Both were also used as paint pigment throughout Europe during the 15th and 16th centuries, not declining in use until the 17th century.

Malachite Room in the Winter Palace of St Petersburg (Hermitage Museum)

In the 1800s, large deposits of high-quality malachite were mined from the Ural Mountains of Russia. Besides being used in jewelry, this malachite was used extensively for decorative purposes. The most notable of these are the Malachite Room in the Winter Palace of St Petersburg (Hermitage Museum), designed in 1830 for the Empress Alexandra, wife of Czar Nicholas I. The room has malachite columns and fireplaces, a large urn, and furniture.

Castillo de Chapultepec of Mexico City, photo by E Vasquez, 2012

Similarly, the Malachite Room in Castillo de Chapultepec of Mexico City has malachite doors along with urns. Other beautiful examples are the Demidov Vase (1819), which can be seen in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York), the Tazza (1910), one of the largest pieces of malachite in North America and a gift from Tsar Nicholas II, in the Linda Hall Library (Missouri).

Demidoff Vase, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

What is interesting about these, and other items from the Russian mines is that the objects are not solid malachite. Natural malachite is too vuggy to cut into very large pieces. Russian artists developed a veneering technique to place thin slices of malachite over metal or stone. The patterns of the slices had to be carefully matched so that the finished object takes on the appearance of solid malachite. These were done so well that it is often impossible to see the joins.

Russian malachite is no longer produced. Today, malachite is mined in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Gabon, Namibia, Mexico, Australia, Morocco, China, Brazil, and Arizona (USA). It is still used in jewelry and some decorative objects. For example, the base of the FIFA World Cup contains two layers of malachite.

HOW

Malachite is considered secondary mineral of copper-bearing minerals. Secondary minerals form when a primary mineral is altered, commonly due to weathering. It forms at shallow depths in the Earth, in the oxidizing zone above copper deposits and serves as a prospecting guide for copper. It should be noted that mined copper is typically a secondary, not primary deposit. The formation of malachite is part of the process of creating that secondary, copper enriched deposit.

Rainwater finds its way through fractures and pores in rocks. As it encounters certain minerals it causes chemical weathering and dissolution. Through time, this forms a leaching zone underground.

In areas where chalcopyrite is found, a primary sulfide mineral, this mineral is dissolved, oxidized, and leached of its metallic ions (Cu2+). The groundwater then carries these ions through the Earth until it reaches the groundwater table. The section above the groundwater table allows for oxidation, but below the table the environment is reducing (no free oxygen). Within the oxidizing zone, just above the groundwater table, metallic ions will precipitate as oxides, carbonates, and sulfates to form secondary deposits. Metallic ions that are not used in these deposits will continue down below the groundwater table, where they will concentrate, react with primary sulphides, and form secondary, supergene copper deposits.

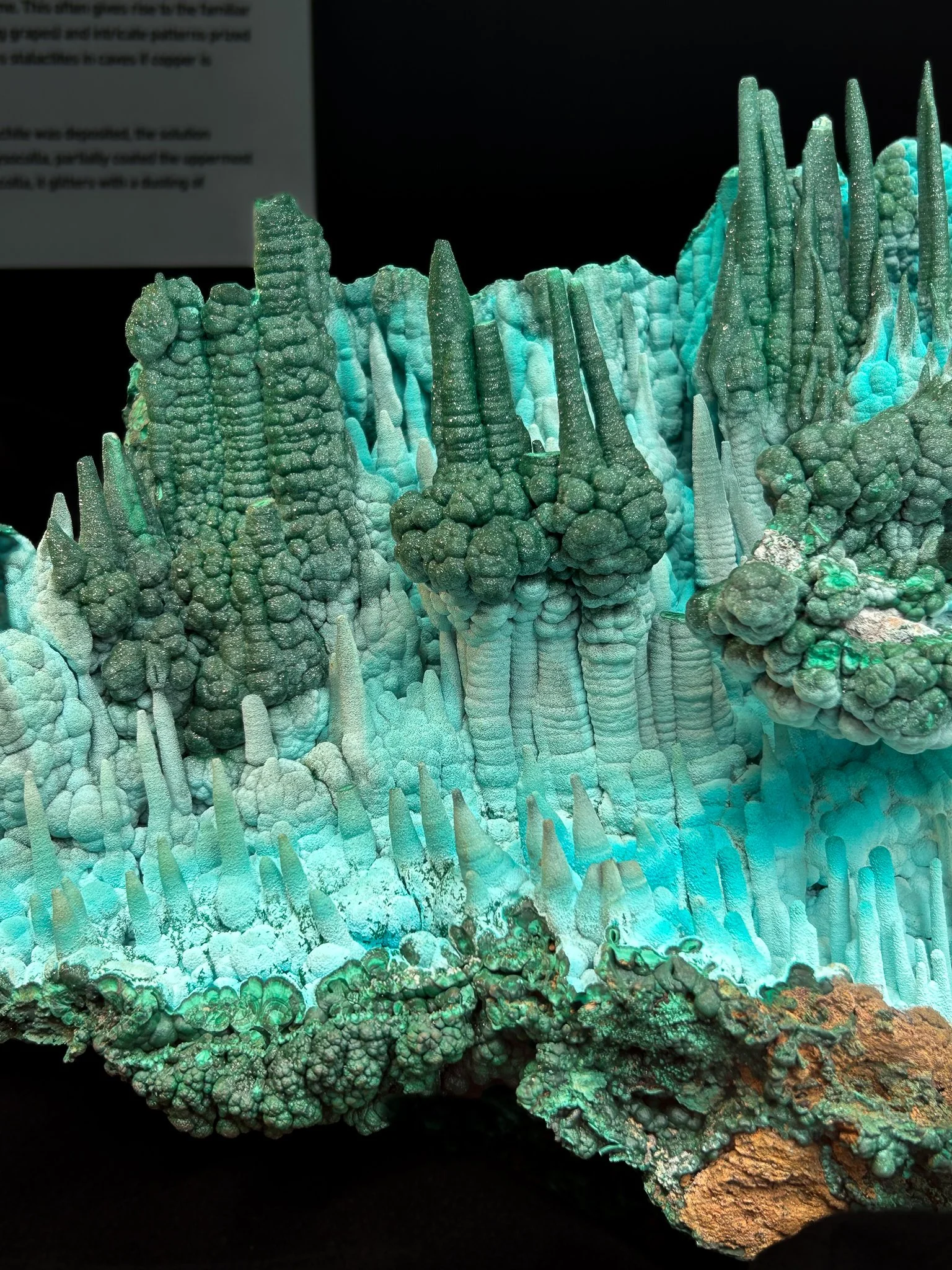

Reconstruction of azurite and malachite cave deposits discovered in Bisbee, Chochise County, Arizona in the 1890's, Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Tucson, Arizona, photo author's own.

Malachite specimn from Bagdad Copper Mine, Arizona, housed in the Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Tucson, Arizona, loaned by Robbie and Bill McCarty (2019), photo author's own.

Malachite, as a copper carbonate hydroxide mineral, requires both copper ions in solution and carbonated water or the interaction with limestone to precipitate. This happens in fractures, caverns, cavities, and intergranular spaces in porous rock. Crystals can form as short needles that fan out radially. But, more commonly, botryoidal (form composed of many rounded segments looking like grapes) or large smoothly rounded, aggregate masses are found. It may also form as stalactites.

"Atlantis" - stalactite specimen of malachite and chrysocolla (sitting upside down) found in the Star of the Congo Mine, Democratic Republic of the Congo, currently housed at GIA Headquarters, Carlsbad, California, photo author's own.

ASSOCIATIONS

Malachite is commonly found with azurite, another secondary mineral of copper that is blue. Azurite and malachite differ only by the ratio of copper to carbonate in their chemical composition. Malachite forms when the copper available is too low to form azurite. The difference between them is slight – one copper ion and one carbonate radical. The end result is that malachite has a more stable molecular arrangement and azurite can easily convert into malachite under the right conditions.

Azurite & malachite specimen, found in Bisbee, Arizona, housed in the Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Tucson, Arizona, loaned by Flagg Mineral Foundation (2011) photo author's own.

During the Middle Ages, both malachite and azurite were widely used as pigments in paintings. Over time however, some of the blue azurite pigment now shows signs of transforming into green malachite.

Malachite replacing azurite, taking azurite crystal form, found in Bisbee, Arizona, housed at the Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Tucson, Arizona, donated by Morris J Elsing (1958), photo author's own.

The most common minerals found in the oxidized zone are malachite, azurite, and chrysocolla. The combination of these minerals is always striking! Some mineral samples have alternating sections of malachite and azurite, forming a gorgeous blue and green stone known as azure-malachite. Specimens of malachite and chrysocolla, or malachite-azurite-chrysocolla are also seen. Eliat stone, national stone of Israel, is a unique mixture of malachite, azurite, turquoise, pseudomalachite, and chrysocolla.

Malachite, chrysocolla, and chalcedony carving from Globe, Arizona, housed in the Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Tucson, Arizona, Loaned by Somewhere in the Rainbow Collection (2019), carved by Jerry Kolesar, photo author's own

GEM CUTTING

oday malachite is most often cut into cabochons or beads. The mined material frequently has small to medium sized cavities throughout the material (vugs). This can pose challenges to the gem cutter. When malachite is mixed with other minerals there can also be challenges in cutting due to variability in hardness between the different minerals. The vugs can cause some issues when setting the stones as well.

The most critical complication a gem cutter must deal with when cutting malachite is the toxicity of the dust generated. inhalation of copper dust and fumes can affect the respiratory tract, liver and kidney function, eye irritation, headaches and muscle aches. For these reasons, gem cutters must use respirator masks while fashioning the stone. However, once malachite is cut and polished, it is completely safe to use in jewelry.

Spectacular malachite boulder showing irregular surface and vuggy nature, found in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, housed in the Alfie Norville Gem & Mineral Museum, Tucson, Arizona, donated by the Bob Jones Family (2019), photo author's own.

TREATMENTS & IMITATIONS

Because malachite is a carbonate, a good test for malachite is effervescence when exposed to cold, dilute hydrochloric acid (HCl). It is one of only a small number of green minerals with this characteristic.

Natural malachite will sometimes be treated with wax to fill small voids and improve its luster. This is considered a non-permanent treatment.

Synthetic malachite is not common. Introduced in the late 1980s by Russians experimenting with aqueous copper solutions, these lab-grown samples were very similar to their natural counterparts. It is not known how long they produced this synthetic material, but currently it is not being produced. In 2010 GIA Laboratory determined that natural and synthetic malachite can be separated on the basis of trace-element chemistry.

Imitation, or fake, malachite is available. These are usually plastic, or resin made to look like malachite. You can usually identify them by low price, non-natural looking patterns, and not heavy enough. Natural malachite is quite heavy due to its metal concentration. Plastic and resin are both very light.

A COMPANION THROUGH HISTORY

Although malachite today isn't as valueable or sought after as it once was, it is still a mesmerizing gemstone and mineral specimen. Now that you know more about it's deep association with human history, you may appreciate it even more!

REFERENCES

Malachite, Hobart M. King, Geology.com

Dr. HZ Harraz, Topic 9 supergene enrichment, Geology Department, Faculty of Science, Tanta University

Miljana Radivojević et. al., 2010, On the origins of extractive metallurgy: new evidence from Europe, Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 37, Issue 11, November 2010, Pages 2775-2787

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305440310001986

David Malakoff, 2021, Ancient Native Americans were among the world's first coppersmiths, Science,

https://sites.dartmouth.edu/toxmetal/more-metals/copper-an-ancient-metal/the-facts-on-copper/

https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/ToxProfiles/tp132-c1-b.pdf